Marking the Eye

A version of this essay first appeared in Issue II of The New Union which is now no longer in existence.

As a poetry pamphlet that bravely announces its endeavour in its title – not easy or conceivable but certainly amusing for anyone who has found comfort in Chris Marker’s filmography – American poet and critic Susan Howe’s Sorting Facts; or, Nineteen Ways of Looking at Marker is, foremost, rigorous in the application of its numbered lenses. That Marker is of interest to a poet is perhaps not as surprising when Howe’s poetic oeuvre is considered. Her fascination with primary texts and scattered, obscured histories is crucial to her work; That This (2010) is a collaged-block-poetry memoir about the death of her philosopher husband Peter Hare, partially ‘a meditation on the eighteenth-century theologian Jonathan Edwards’s family archives’, according to Maureen McLane who interviewed her in 2012, whereas My Emily Dickinson (1985) is a compact, lyrical ode to the poet as much as it is a much-needed poetic affirmation of the social conditions of Dickinson’s writing.

Howe is often said to belong to the school of Language Poets, a movement of poetry that began in the 1970s focussing on destabilising the conventional conditions of language-making and, in turn, engaging the reader as an active subject in the production of meaning. Other Language Poets include Lyn Hejinian, Bruce Andrews and Bernadette Mayer. Howe’s obsession with the visual is reflected in Sorting Facts too; Howe works traditionally with collage, images, block-texts of verse that play heavily with spacing, line-breaks and other poetic devices but in writing about a filmmaker – especially one who remained out of public view for most of his life – and engaging so deeply with two of his works, the scope of the visual in her work itself is altered magnificently.

Most of the nineteen sections in the pamphlet of what I will reluctantly label prose-poetry begin with approximations of epigraphs. Some are quotes, confident in their form, borrowed from voices ranging from French philosopher Levinas and the protagonist of Sans Soleil, Sandor Krasna, to poet Walt Whitman. Others briefly nod at the tasks they wrestle with; section XVI opens with ‘Film-Truth’ and tries to formalise what we know about the filmmakers named Chris Marker and Dziga Vertov (‘Dziga Vertov and Chris Marker are pseudonyms’, she writes) while ‘The Negative of Time’ for section X reveals what we may imagine to be a portion of a letter to her deceased husband’s parents written from New Mexico, where she tries to summarize her life as a cadet in the desert-country, detailing its sunrises and a dream of life made with more time (‘But when we get into bigger airplanes and they have a range of thousands of miles which they can travel in a relatively short time it will be better’). Still others, such as section XVIII, begin without preamble. Howe’s reach back into the archives is wide but she is also well-attuned to the uses of mixed media; the stills from Marker’s films are tantalizingly placed across the pamphlet, leading us to focus on the image with an attention that is not misplaced from the verse.

Marker, who died on 30 July 2012, was born on 29 July 1921. His birthdate is not mentioned by Susan Howe, whose brief biography of Marker in section XVI is remarkable for perfectly mimicking what is arguably a trademark Marker style of narration; acknowledging a subdued but ferocious fidelity to distorting what is conventionally ‘fact’ because facts are not useful without the imagination. ‘Christian Francois Bouche-Villeneuve was probably born in the Paris suburb of Neuilly-sur-Seine in 1921 possibly to a Russian mother and an American father’, Howe writes. ‘Other possibilities for a birthplace are Ulan Bator in Mongolia, or Belville, the Arab quarter of Paris.’

She goes on to add that ‘he may have served as a resistance fighter during the occupation of France, some accounts claim he also joined the United States Army as a parachutist – he says he didn’t’. As the biography wears on, she fixes the tense and does away with the imagining: ‘After the war Marker played music in bars’, ‘He also wrote a wartime aviation novel’, and the last sentence runs on: ‘Marker was founder, editor, and writer of the Planet series of travelogues for Editions de Seuil, which blended impressionistic journalism and photography Marker turned to documentary filmmaking in the 1950s’ as though the facts are being gulped down, unpleasantly, before returning to reassure us with a line-break: ‘These are only some facts.’

The desire to gaze at Chris Marker’s aesthetic is not an unusual one since his persistent desire to present you with the camera as the eye you must trust is what makes his films so terrifying and joyful – particularly La Jetée and Sans Soleil (orSunless), the ones that Howe primarily focuses on. Sans Soleil is a 1983 bricolage of documentary footage from Iceland, Cape Verde and Tokyo, amongst other places, dreamily coupled with a voiceover by Alexandra Stewart (identified as ‘exaggerated in its accentlessness’ by Howe) who reads out the letters of protagonist Sandor Kransa and ‘electronic sounds’ (according to the credits of the film, arranged by someone named Michel Krasna, constituting possibly the only instance in western cinematic history of a fictitious character arranging the score of a film). Early on, Krasna films the residents of Fogo, in the Cape Verde islands, waiting for a boat at the jetty. His camera catches them looking at him warily, occasionally laughing, while they go about their daily business and he is forced to write, ‘Frankly, have you ever heard of anything stupider than to say to people as they teach in film schools, not to look at the camera?’

Krasna is often said to be Marker’s avatar, and it is moments like these that Howe seems to love best, moments where ‘we aren’t sure who is real or imaginary’. She loves them, it appears, because the quiet authority of illusion in Marker’s camera mirrors her own confrontations with the (borrowed and negotiated) memories of her dead husband, her childhood moments in movie theatres in Cambridge, MA and readings of other filmmakers who interest her, such as Tarkovsky and Vertov. ‘We are as real and near as cinema’, she writes. Marker’s eye is omniscient and important, even if it is a lie.

In the 2012 Paris Review interview with Maureen McLane, Howe confesses that her biggest regret in life was not going to university. In reaction to McLane’s evident surprise, Howe cites her ‘autodidact’ self, and explains her disenchantment with disciplined boundaries. ‘I get these obsessions and follow trails that often end up being squirrel paths’, she says. ‘There are huge blanks.’ Sorting Facts is a delightful demonstration of these blanks, and Howe is unapologetic about her stream-of-consciousness narration, and where it leads her; it is as if Marker’s roving eye has granted her the license to wander between times and people. I imagine Sandor Krasna asking: ‘or was it the other way around?’

In section XI, a near-straightforward analysis of the characters in Tarkovsky’s Mirroris interrupted by:

Distant woods beautiful auspicious morning at evening a sudden west wind soughing through white flowering meadow. Facts are perceptions of surfaces.

This tendency to describe a moment from life or a scene in a film and almost inevitably follow it up with a question or observation about how sight (or perception, or depiction, or facsimile) is as treacherous as memory, is a recurring design in Howe’s pamphlet. Its fragmentary nature of enquiry is possibly a response to the unrelenting gaze of the camera and its subjects in both La Jetée and Sans Soleil. Sans Soleil is my personal directory of desire; I have watched it innumerable times, in various permutations, sometimes muting the sound while letting the images – beautiful in their devotion to independence – flood me, and on other occasions, falling asleep to Stewart’s rich voice and Krasna’s haunting words in pitch-darkness, trying to pretend the letters were written to me. Marker’s ability to grasp at the heart of the despair/desire dichotomy in a world where he (or Krasna) sees ‘the function of remembering’ as ‘not the opposite of forgetting, but rather its lining’ is one that forces us to be vulnerable to him. Susan Howe has a similar effect on you when she discovers that the real time of emotion isn’t musical time or background noise of civilization or continuity of exposed film. You can always tell memory, not the coverings it closes first.

What lies beneath memory, then? The struggle to remember precisely is as painful – or plain misguided – as it often is simply because memory itself is discarded in the process to see deeper, or further. Howe is not as interested in what can be remembered – namely, what can be proved, trusted, named and seen – as she is in the ways we try to see what is lost to us.

I find Howe’s text is to be approached with the eager but cautious affection that we have towards Marker’s films, perhaps like one would read Benjamin’s Arcades, or Maggie Nelson’s elegy to Blue, Bluets: a dictionary to be dipped into, when in need of instruction, mercy or wonder. All are compelling and methodical in their desperation to make you see, not like them, but to adopt gazing, viscerally, as a mode of being. Howe’s involvement with particulars of scenes means she sees them again, as she writes the scene out, as text, and we are simultaneously watching both her watching these divorced scenes, and our own memories or imaginings of it unfold. Howe writes: ‘What do you see camera? / Shouts and not memorized.’

Before Sorting Facts is obsessed with facts, it is devoted to sight, or learning how to see. In a particularly moving section, she recounts how, since her second husband David’s death, she is able to look through photographs of him but not at videos – he is almost too alive for her, it appears, and it is easy to imagine her being overcome by moving images since she easily replaces one eye (hers) for another (the camera’s). She remembers the last summer they spent together, when he was unable to look at ‘recovered black-and-white moving documentation’ of his mother Bae reading and playing with his daughter Lisa, without weeping. The tense shifts to the present: David is evoked, as a being who crawls into the present because the gaze of the camera has panned; if he was watching Bae, Howe is watching him now, filing the memory back into the format of active memory when it has passed by, again:

Sometimes he and Lisa’s mother are playing in the sand with their daughter. Sometimes he stands at the door of his studio then goes inside. He designed the building himself. Now it has been torn down. I can only perceive its imprint or trace. Lisa remembers listening to the noise of waves breaking over pebbles in the cove at night, how tides pulled them under, how they swirled and regrouped in the drift and came back. I imagine the noise as fixity gathering like a heartbeat, steady and sure.

At this point, Howe isn’t only remembering her husband. The heartbeat she alludes to is a device that Chris Marker briefly uses in Sans Soleil, as a transition moment, perhaps even as a continuation of memory taking on different forms. If Howe is grieving for her husband, she is grieving through the eye of Chris Marker. Chris Marker has himself been made into a function of remembering.

Howe speaks explicitly – even reverently – of Marker’s sight later in the pamphlet. In section XIV, she confesses that ‘in La Jetée and Sans Soleil, as in a play by Racine, glances are the equivalents of interviews. A look can be an embrace or a wound. Even the gaze of statues.’ It appears as though Howe has taken unconsciously to looking as a grieving habit when she starts writing the prose-poem, but has grown aware of it by the end – after giving in to it – when she is writing exclusively about Marker, Tarkovsky and filmmaking itself.

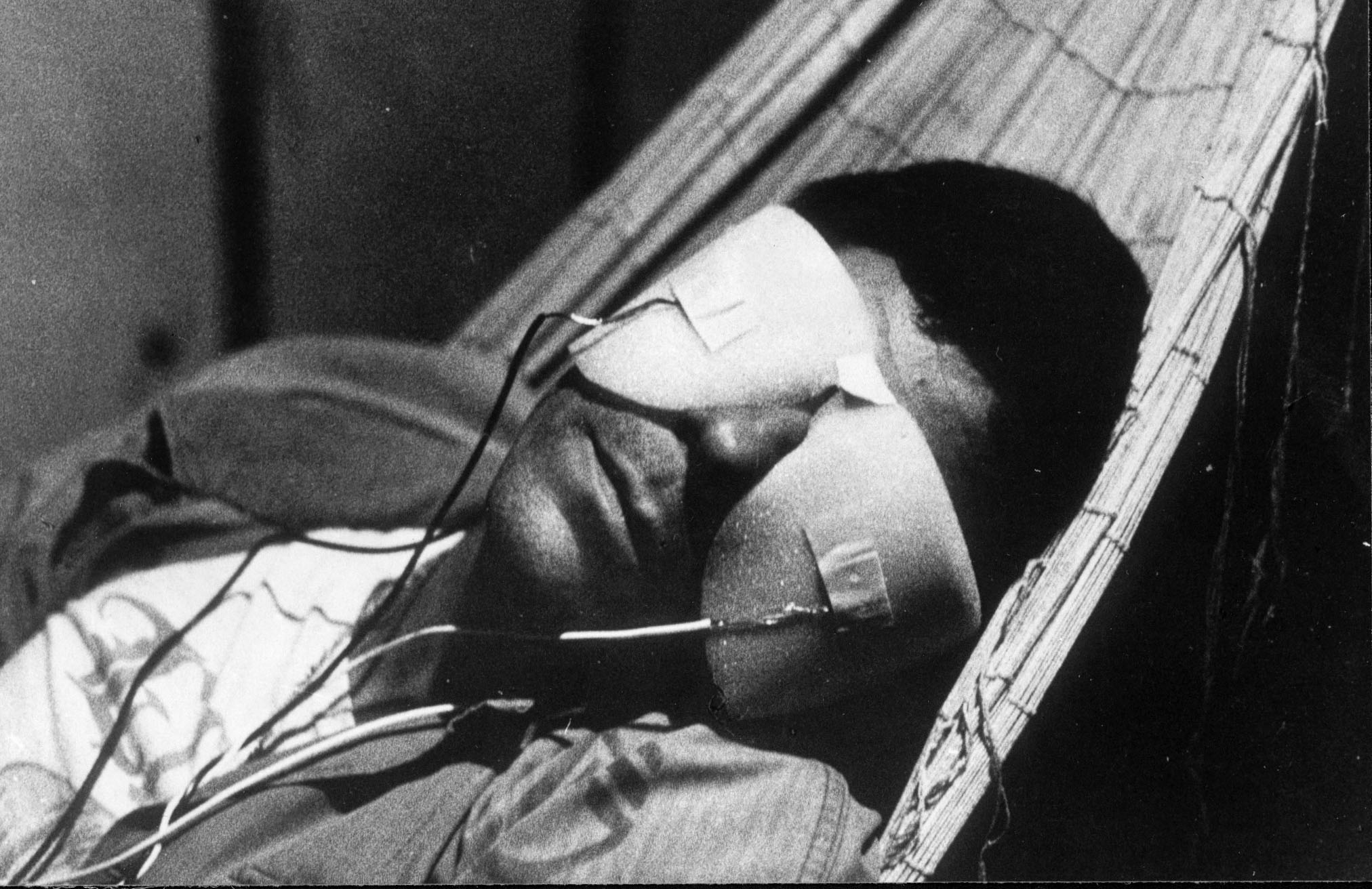

La Jetée – described as a ‘photo-roman’ in the opening credits – is a short film about a time-travel experiment comprised entirely of stills, set during an imagining of World War III. It tells the story of post-war Paris, when time-travel is being tested on various survivors. Most of them fail to survive the shock of travel but one man makes it repeatedly back to the pre-war period with a single memory-image that helps him travel through time. By the end of the film, it is not only revealed what the relationship between the image and the man’s life is, but also that our ability to confuse time – to pretend the past is the present and to seek the future as a substitute for the present – can have destructive consequences.

The real beauty of La Jetée is not its elegant treatment of time-travel, but how it recognizes the shockingly personal veracity of mistaken memories, what Howe calls ‘a compelling documentation’ of connections between ‘lyric poetry and murderous history’. Long montage sequences in the film are devoted solely to men and women looking; looking at gardens, at the skies, at the past, at each other. The connections Howe makes between ‘fact’, memory – which is neither purely fact nor imagination – and her deep, astute readings of filmmakers like Vertov, Tarkovsky and, of course, Marker are not very different from Marker’s own cunning process of documenting what is pleasurable to his eye.

In section V, when she remembers the still of the boy gazing at the young, smiling girl in La Jetée at Orly airport in Paris – strands of her hair blowing in the wind and across her face, her fingers curled into a question, resting on her lips – Howe tries to guess: ‘Her pensive gaze is wary tender innocent dangerous. She may be remembering beckoning staring apprehending responding reflecting or deflecting his look.’ Below the text, the photograph of the smiling girl is reproduced. We, as readers, are invited to conspire in the making of the gaze – the choice to deflect is not offered because the premise is to participate in the act of looking, and to remember that we, too, have made a secret habit of looking.

‘Some of my earliest memories are film memories confused with facts’, she admits in section VIII. It seems at several points in the pamphlet that Howe is trying to separate memory from fact, before collapsing the two into a lens that she appears to trust more. A heavy interrogation of the dictionary meaning of the word ‘document’ appears at the beginning, following a journalistic account of Dziga Vertov’s concerns about the fading of ‘documentary poetic film’. At the end of such a meticulous exercise in note-taking, she situates her own work as that within the form of ‘poetic documentary’: a classification she adopts only after she tries to write about two of Marker’s films. Howe is giving herself the license not just to remember inaccurately – a necessary self-kindness often hindered by hubris on our part – but also to qualify what she does remember as a feat of imagination, as a way of experiencing the world, much less holding it accountable as ‘objective’ truth.

What does poetic documentary consist of? Research, evidently, which is familiar territory for Howe’s work – she has read copiously on Marker’s cinematic predecessors for this particular project – and a ferocious re-watching and re-telling, often scene-by-scene, of Marker’s films. Most importantly, it consists of fact aspoetry: poetry as testimony, poetry as a form of documenting memory. Howe often extrapolates from Marker’s world to her – our – own, making language itself the center of play:

According to the narrator of Sans Soleil, the baffling part of the Japanese Shinto ritual of Dono-Yaki is that circle of little boys we see shouting and beating the litter of scraps of burnt ornaments or votive offerings with long sticks after the flames have died down. They tell him it’s to chase away the moles. He sees it as a small intimate service.

In English mole can mean, aside from a burrowing mammal, a mound or massive work formed of masonry and large stones or earth laid in the sea as a pier or breakwater. Thoreau calls pier a ‘noble mole’ because the sea is silent but as waves wash against and around it they sound and sound is language.

This, here, is the breakdown of language itself; Howe is doing much more than making the mole-animal-sea-sound association for us. She is handing over a new vocabulary as an accompaniment to Marker’s non-fiction, and the worlds embodied therein: many seas, many more sounds, infinite languages. Consider the latter half of Sans Soleil, which runs in sporadic bursts of terrorising but strangely panoramic soundscapes, mismatched against a barrage of videogame images – and more, until we dissolve into Hitchcock’s eye. We are re-making Chris Marker’s particular brand of evasiveness into a curio that falls into our line of vision when we step out of the film and into the world. We are doing this with Howe’s simple movement from something small – a specific, contextualized ritual in Japan – into a larger wave of being. It is impossible to see the same scene without falling back on the sounds of the words, and our memories of them, to see without desperately believing.

For Howe, Chris Marker is first and foremost a poet. Marker was not alien to poetry; in Sans Soleil, Sandor Krasna quotes Basho, and in 1984, Marker composed a ‘video triptych’, according to Catherine Lipton in her book Chris Marker: Memories of a Future, titled Three Video Haikus. The three short videos all deal with a moment of ironic solitude in a specific locale, or around a person. Tchaika, for instance, strings together treated images of the river Seine flowing past a bridge and trees, but its final shot freezes the silhouette of a bird as the river rushes past. This peculiar brand of bricolage, where a sharp eye draws attention to the peculiar charms of the world as much as it does to itself, in its process of watching, is common to both Howe and Marker. They are bricoleurs who watch the spool of memory unwind itself to the end without caring for its conclusion, only for the eccentricities of language.

The last line of the pamphlet, in section XIX which is epigraph-less, conflates ‘refused mourning’, as a reading of an extract from Vertov’s Kino Eye, with the camera. Howe does not refuse to mourn in Nineteen Ways of Looking at Chris Marker, but when she submits to the images she attempts to work her way through, her grief is no longer suspended in the place of grief. It transforms into a way of looking at the world, a pair of viewing glasses that she may never discard because they are now being held on their own terms. We may, much like Howe, not be entirely sure of what we are looking at when we decide to look, but it is essential that we persist in looking, long after we have given up our search for ‘facts’. These nineteen ways of looking at Chris Marker become – like all powerful poetry that comes into the world intending to comment on it and quickly becoming of it – not about Chris Marker by the end of the pamphlet. They are nineteen ways of looking, and nineteen ways to embrace an act that we are taught is simultaneously of great consequence and great pain.